Written by Alex Schneider, Website Editor

Saturday, July 3, 2010

Samuel Edward “Eddie” Hatch—my grandfather—has lived 84 years, yet none was as pivotal in the story of his life as the year 1944. For 18 years prior, my grandfather had lived a quiet life in a small town in Western Massachusetts, in the home of first generation immigrants of modest means, until the Army of the United States of America changed the course of his life. On Nov. 3, 1943, my grandfather became Samuel E. Hatch, Technician Fourth Grade of the 130th Chemical Processing Company, and was sent south to Alabama for basic training. Within months, my grandfather had toured the world, moving through one of the suburbs of London known as Chelsea, the volatile countryside of Alsace-Lorraine, and the small island of Luzon in the South Pacific. Twenty-seven months and 12 days later, on Jan. 25, 1946, my grandfather returned to Western Massachusetts, where he resides to this day. Nevertheless, of all the moments and memories my grandfather carries with him, the images of 1944 are the most real and deserve the greatest attention. In the spirit of the army barracks tune, “Old soldiers never die, they just fade away,” my grandfather says, “Old soldiers never die, they just keep telling war stories.” Young Eddie’s story —told too many times to count —focuses on one year that, at least in my family, has yet to fade away.

For the first time in his life, in 1944, my grandfather spent New Year’s Day without family; he was stationed at Camp Sibert, Ala., one of the largest training grounds for the Army’s Chemical Warfare Service (CWS). A training reservation of more than 70 square miles, Camp Sibert was opened in mid-1943 for what the military’s history of the CWS called “one purpose only: to facilitate the training of chemical troops” (1). Accordingly, by the beginning of 1944, my grandfather had spent five weeks learning about chemical components at Camp Sibert, while also undergoing physical basic training. In a letter dated Sunday, Jan. 2, 1944, my grandfather described for his parents what he had been learning: “This past week, we studied about chemical agents. … This past week was practically all class work, tests, problems (figuring the amount of chemical ingredients in suspensions, solutions, etc) and lectures. I enjoyed very much [sic], and today I am reading over my notes” (2). Induction into the army would last through April. During this time, my grandfather realized he would not be on the front lines fighting; instead, as he explained in an interview in October 2009, only when “the enemy used gas warfare would we go to help our troops.” Indeed, my grandfather was in a chemical processing company that, according to the Military’s official history of the war, “was to keep available to theater chemical officers a supply of permeable protective clothing … impregnated with chlorinating compounds so as to protect the wearer from the effects of vesicant vapor” (3). My grandfather has a different way of describing his role: “This is all moot —m-o-o-t —because the enemy did not use gas warfare.” The Military’s history of the war describes this fact in more diplomatic terms: “The CWS … felt the full impact of preparing for a kind of war which was not being fought while contributing significantly to the war which was being fought” (4). Indeed, the months my grandfather spent at Camp Sibert did not prepare him for later experiences, since the axis powers never used chemical warfare. Whether or not the time in Alabama was wasted or “moot,” the simple fact remains that, as my grandfather said, “We never did the work for which we trained.”

Finally, in April 1944, my grandfather and his company left Alabama and went to Camp Kilmer, N.J., where they awaited transport to the war zone. On April 22, just before leaving, my grandfather spent a night at the Stage Door Canteen, an experience he most certainly would have forgotten had it not been for the sketch artist Irwin J. Weill who captured my grandfather’s portrait on a flimsy sheet of paper. The most striking aspect of the picture is how young my grandfather appears, certainly not the typical army entrant. His hair is combed neatly and his army jacket seems to shine, displaying prominently the acronym “U.S.” and the symbol of the CWS. And yet, even at that formative moment on the eve of my grandfather’s departure to the front, he looks off into the distance with a forlorn stare still characteristic of him when he describes the events of 1944. This image captures the contradictions that define my grandfather: He is a patriot who believes World War II was “a just war,” even as his pensive glance reveals his skepticism.

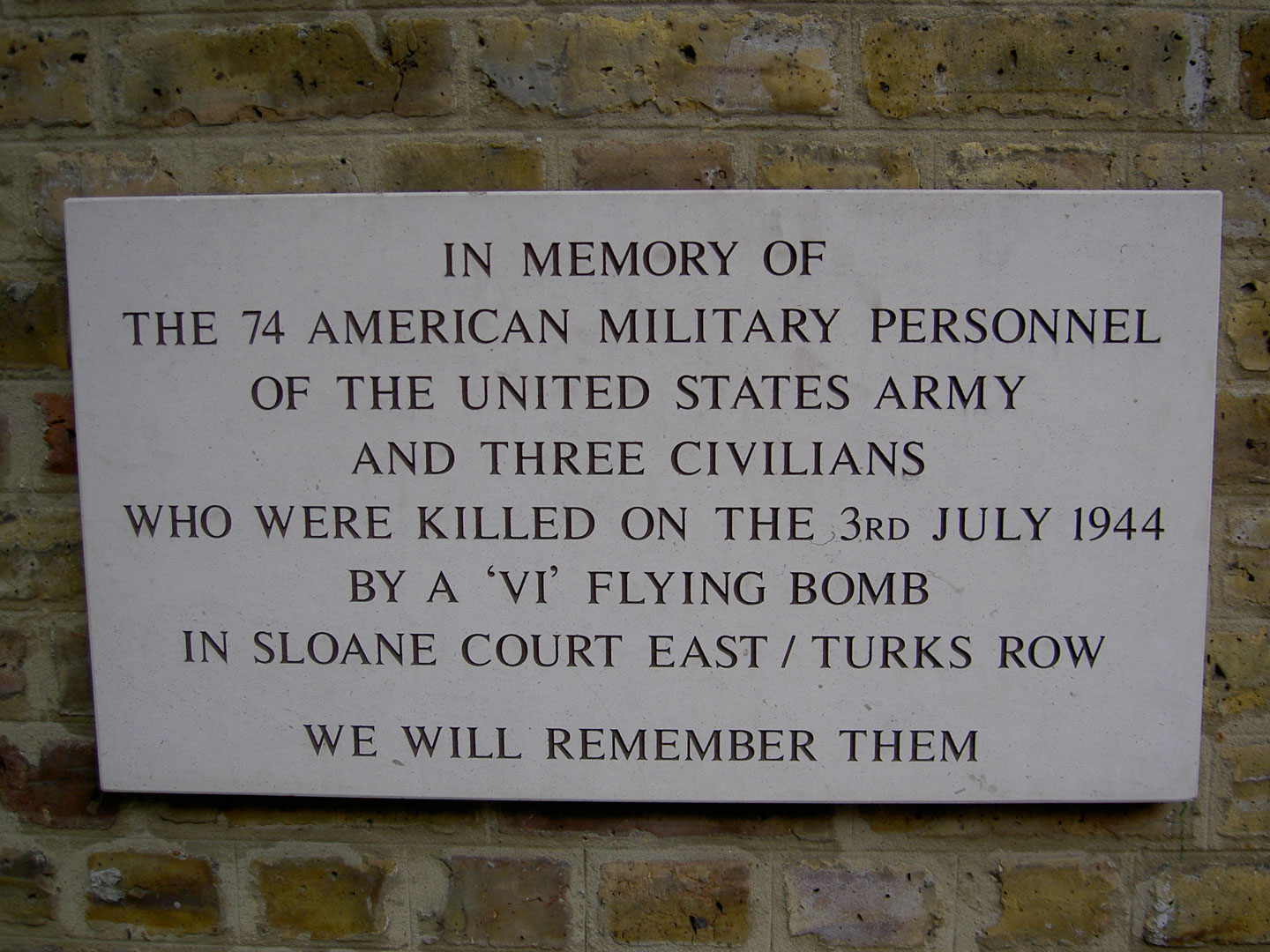

Finally, on May 6, 1944, my grandfather arrived in the United Kingdom and was billeted on Sloane Court, a street in a former residential area in Chelsea, London. He remembers learning of the D-Day invasion in June but, keeping with the mission of his company, he remained in London. On June 18, my grandfather wrote a letter home describing the state of war in the city: “We have been having a few air raids lately, because of the robot planes sent out by the [Germans]. They are nuisances, and as yet have not caused too much damage” (5). Ironically, the unthinkable took place just 15 days later, when, on Monday, July 3, the “nuisances” my grandfather had described in the letter —V-1 flying bombs —hit home. That morning, my grandfather and his friend, Theodore “Teddy” Booras made a pact: They had been assigned clean-up duty for the week, and they decided that they would each day alternate carrying the trash down the stairs to the cellar of the building. Teddy volunteered for Monday, and on that fateful day he carried the trash to the basement as my grandfather exited the building. Once outside, my grandfather attempted to board the truck that was waiting to bring the soldiers to their workstations but, by chance, the truck was full. That’s when he heard someone yell, “buzz bomb.” My grandfather’s reaction was immediate: “I ran to my left, and I saw my mother’s face in my mind. I ran, and I hit the ground. I was thrown up against something. That was it. I lived and he died, that’s the story.” The bomb decimated my grandfather’s chemical processing company, killing all the men on the truck, the commander of the company, and Teddy Booras in the basement of the billet. Today, a small, stone plaque commemorates the destruction, reading, “In memory of the 74 American military personnel of the United States Army and three civilians who were killed on the 3rd July 1944 by a ‘V1’ Flying Bomb in Sloane Court East. We will remember them.”

For the remainder of the year, until January 1945, my grandfather remained in England, recuperating as new men joined his company, which was preparing to be relocated to France. Although my grandfather was banned by military censorship from telling his family of the bombing lest the Germans discover their V-1 bombs had succeeded, his letters home, including one sent Sept. 7, sound forlorn and nostalgic when compared with the more energetic tone that filled earlier letters from Alabama: “Well, my dear parents, take care of yourselves; get out and enjoy yourselves. When you come right down to it, everyone has about the same types of problems these days. We’ll all be home as soon as we’ve rid the world of these beasts” (6). Writing these words at age 19, my grandfather sounds as patient as the 84-year-old man who tells the story today. The bombing, without a doubt, had changed my grandfather’s perspective on the value of every moment of life.

For the remainder of the year, until January 1945, my grandfather remained in England, recuperating as new men joined his company, which was preparing to be relocated to France. Although my grandfather was banned by military censorship from telling his family of the bombing lest the Germans discover their V-1 bombs had succeeded, his letters home, including one sent Sept. 7, sound forlorn and nostalgic when compared with the more energetic tone that filled earlier letters from Alabama: “Well, my dear parents, take care of yourselves; get out and enjoy yourselves. When you come right down to it, everyone has about the same types of problems these days. We’ll all be home as soon as we’ve rid the world of these beasts” (6). Writing these words at age 19, my grandfather sounds as patient as the 84-year-old man who tells the story today. The bombing, without a doubt, had changed my grandfather’s perspective on the value of every moment of life.

When he discusses the bombing of July 3, my grandfather inevitably talks of chance. “What were the odds?” he asks. “We could have been billeted anywhere else in London, but we were billeted right there, right there where a V-1 flying bomb stopped right there on our street. … It could have stopped anywhere; it could have stopped over Buckingham Palace.” The odds were unseemly. My grandfather had been in London less than two months when devastation struck, but those two months and the many that had laid ahead pale in comparison to the one morning my grandfather faced true active combat. Indeed, while the year 1944 was, without any doubt, a critical time filled with new experiences and travels for my grandfather, the year truly began and ended for him on July 3.

Bibliography

Brophy, Leo, and George Fisher. The Chemical Warfare Service: organizing for war. Washington, D.C.: United States Army. 1959.

Hatch, Samuel E. Personal Interview. 24 Oct. 2009.

Hatch, Samuel E. Collection of letters written to parents. 2 Jan. 1944, 18 Jun. 1944, 7 Sept. 1944.

Kleber, Brooks, and Dale Birdsell. The Chemical Warfare Service: chemicals in combat. Washington, D.C.: United States Army. 1966.

Footnotes

(1) Brophy, Leo, and George Fisher, The chemical warfare service: organizing for war (Washington, D.C.: United States Army, 1959), 272.

(2) Hatch, Samuel E., Letter written to parents, 2 Jan. 1944.

(3) Kleber, Brooks, and Dale Birdsell, The chemical warfare service: chemicals in combat (Washington, D.C.: United States Army, 1966), 304.

(4) Ibid, 637.

(5) Hatch, Samuel E., Letter to parents, 18 Jun. 1944.

(6) Hatch, Samuel E., Letter to parents, 7 Sept. 1944.

Copyright information

The above academic work was published on July 3, 2010, on the 66th anniversary of the bombing in Southern London. Reproduction or distribution of any material on this page is strictly prohibited without the express permission of the author, which can be requested using the contact page on this website. All rights reserved. You may download and reference material from this website for your personal, noncommercial, or educational use only.